When it comes to posture and stability the way you breath plays a crucial role as breathing and posture form one functional unit. That is why, when working with anyone who has musculoskeletal issues and generally any movement difficulties, we almost always start with the breathing pattern assessment.

How are they connected?

A breathing assessment is not about testing your respiratory capacity but more about the breathing stereotype you use and how it affects your posture. Our breathing pattern gives us a direct clue about how the muscles of our deep stabilization system, particularly the diaphragm, are functioning during any activity.

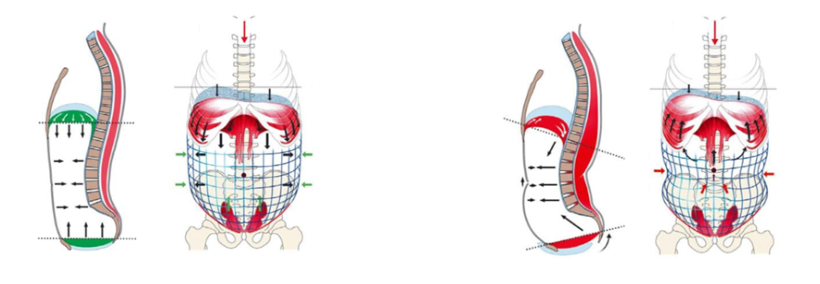

When we talk about postural stability, we are usually talking about the ‘’core’’. The core is defined by the muscles of the deep stabilization system which include deep neck flexors, abdominal and pelvic floor muscles, the diaphragm and short spinal extensors. Only when there is a proportional activity of these posterior and anterior muscles, that ideal stabilization is achieved.

Since the diaphragm plays the central part of both functions, our breathing and our postural stability, it becomes a key focus. In an ideal breathing pattern, our diaphragm would contract as a whole and move downwards and out to the sides via its attachments. The lower ribs expand and there is also an increase of intra-abdominal pressure created. We observe this as an expansion of the abdominal wall to all directions symmetrically.

In a dysfunctional breathing pattern, the diaphragm may not be utilized well enough for such an expansion and stability to occur. For example, typically in chest breathers, only the posterior part of the diaphragm is moving downwards. In this case, the ribcage is not well positioned and the ribs tend to flare up and out. This means that the muscles of the deep stabilization system are compromised, and they are unable to counteract the actions of the upper chest and neck muscles. This later on can present itself as tightness of the neck muscles and stiffness of the mid-back.

The developmental perspective

As early as 3 months of age, the diaphragm’s postural function begins to kick in. As the breathing pattern begins changing, the baby’s chest shape changes as well. We finally see a successful achievement of this postural stability by a baby’s ability to lift off their legs and hold them up in the air while on their backs, and later when they begin to turn to their side by 4,5 months of age.

These milestones would not occur timely nor in good quality if any of the muscles or their development are unideal or compromised.

Where do you begin with your breathing self-assessment?

Checking the way you breathe is easy. Ask yourself the following question and observe your usual breathing pattern:

- Does your tummy rise as you inhale?

- Do your ribs expand down and outwards to the side?

- Or do you observe the opposite, your tummy going inwards with breathing in?

- Do you find yourself holding your tummy inside to ‘’slim’’ your waistline?

- Or do you breathe more to your chest, feeling your shoulders moving up as you inhale?

Answering ‘yes’ to either of the last three questions can be a sign of an insufficient breathing stereotype. For more practical recommendations on how to counter it read our next article.

Mgr. Farah Droubi